OUTSIDE IT’S RAINING, THE KIND OF slick, greasy rain you only get in cities. The atmosphere is oppressive. Inside the Brewer’s Inn, Wandsworth – a one-time haunt of Peter Green back in the days when he frequented the DSS building opposite – it’s warm and relaxed. Green slips in unnoticed, following in the wake of his manager, Stuart Taylor, who scopes the place out Secret Service-style before settling Green into a chair and disappearing to the bar.

“Hello, I’m Peter,” says Green, his face cracking into a nervous semi-smile. For a brief moment it’s just me and Greenie, the living legend, face to face, staring blankly at each other. “You used to come here in the ’80s, didn’t you?” I say, for want of anything better to break the ice. Green looks confused momentarily and you can see him casting back through memories of that earlier person for any vague recollections.

“Might have done, it’s difficult to say, but I reckon it’s all changed in here from the olden days. Used to have a big fire in the corner and a jukebox that had Little Richard on it.” Green has the tone of a genial but somewhat distracted pensioner recalling the days of music-hall, nutty slack and chips at tuppence a bag.

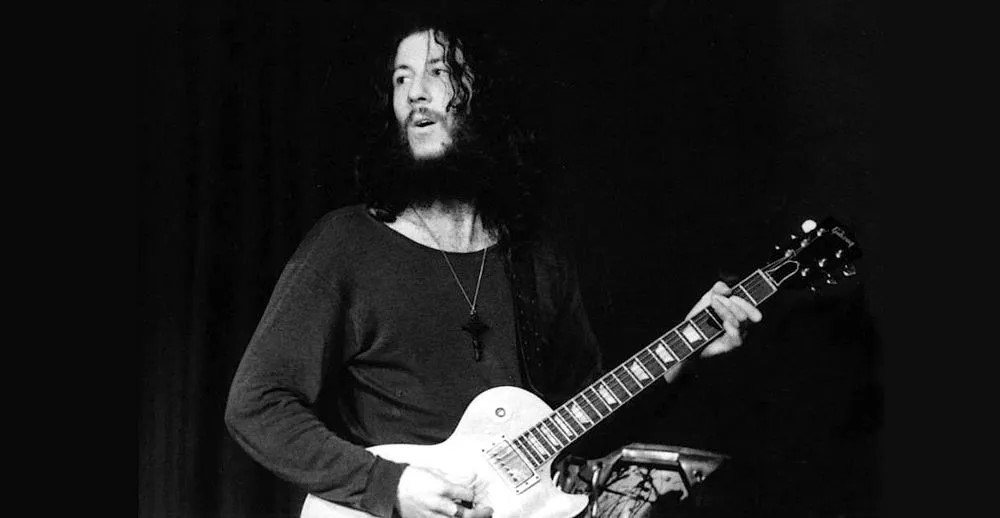

“He’s great on the ’60s. Last week’s more of a problem,” Taylor had told me. As Peter talks you realise there are great chunks of his life that simply made no entry in his memory Sitting back on his chair he stares around the room like a child. No-one stares back. But then why should they? Green today is far removed from the sinewy, bushy-haired man of old: portly balding, wisps of wiry, grey hair shooting out from either side of his head and long, deep furrows across his forehead tell their own story.

Two things strike you immediately once you’ve got over the change in Green’s physical appearance. The hands, feminine, alabaster white and without a single gnarled vein or knot are unlike any hands I have ever seen; long and elegant nails perfectly manicured, tapering to fine delicate little arcs. These are the hands of an artist. Green periodically uses them to gesticulate for wild periods as some idea floats back, but for most of the time they lie inert on the table top.

The other striking features are the eyes. Piercing, olive discs, clear and bright and seemingly giggling in their sockets. Peter Green is a funny man; it’s a twisted, often unfathomable, internal comedy logic that occasionally borders on the painful. But for the most part, Green is at ease with himself and his own troubled past. There are no barriers and he has nothing to hide. Even when talking about the most painful moments, as when describing his LSD experiences and the madness they triggered, he is charming and self-deprecating. In fact, as he talks away, it strikes you that he appears to find his own past curiously amusing. He seems as relaxed and contented as any man who has been through the mental wringer can be.

Half an hour in, he stands up suddenly and asks if he can have a bottle of stout. “They don’t call it stout anymore, Peter,” says his manager. “Oh, don’t they? I used to like a nice bottle of Mackeson’s meself.” He peels a fiver from a fat little bankroll in his pocket and insists on buying everyone a drink. “You have no problem with carrying money about you these days?” I venture. “I never really did,” he cackles. “I just thought I did. I like money now; I want to have a lot more of it. I wouldn’t give it all away anymore.” His face breaks into a wily grin that says, ‘Don’t take me too seriously’, and he settles back into his chair, bottle of ale clutched in his long white hand.

Every now and then, for the briefest of moments, Green’s face takes on a hunted look and you can see the fear enter him. Most of the time, however, he is just good company: a deeply passionate, sensitive man who still believes that music is the reason he’s here. “Words get in the way. The music is actually a more precise way of telling someone something. Music is the words, that’s the way I speak…until it gets too deep into your soul then you just have to stop and go to bed. But even there it doesn’t go away…”

Who made you first want to play guitar?

Hank Marvin was my first guitar hero. In fact, I should be playing on a tribute album to him soon. It wasn’t how you think of The Shadows now. They were very, very hip then. I listened to his playing because it was very lyrical, his phrasings were melodic and I’ve always liked a nice melody. Hank made the guitar into an instrument that talked colours. I know Cliff was meant to be England’s Elvis but we were all looking at Hank, to be honest.

I also used to enjoy that bloke [Cliff Gallup] from The Blue Caps, Gene Vincent’s band. Good, solid but very simple player. I don’t like too much complication; it’s like unnecessary words. I don’t use the word ‘lick’ – I hate that word, actually – because I don’t play licks, I play phrases or riffs. A riff is a short thing that you repeat and a phrase is a group of notes for your melody. I’m big on melody, I am. I’d like to do the standards one day, the kind of stuff that people can sing down the pub or to their bird.

Hendrix was special ‘cos he had everything. He was worthy on every level, wasn’t he? He tickled your soul with his playing. He had the understanding. Someone like me didn’t have nothing of what he had. I was just a working-class kid who lived in Putney.

Sumlin and Wolf had it. No-one knew what he was on about half the time but it made sense on another level. Sumlin’s playing was what we all wished we could be like, not just for what he played but where it came from. You can just tell the people who understand the blues.

I was playing some Wolf just the other day, ‘Spoonful’, ‘She Gave Me Water’. I mean, what does that mean? I didn’t understand the blues well enough to play it, so I stopped. The blues was too deep, it was too painful. See, the guitarists who copied them old black players were doing an interpretation but they couldn’t get to the feeling behind it because none of us had that experience. It sounded OK for a while, until you started to realise that the blues is something you spend a lifetime in. There’s levels that most people, including me, never got anywhere close to.

It got much too deep for me and I got lost; it ended up hurting my soul so I stopped it and started to make stories up instead. All my songs after I stopped playing blues were stories.

How does it feel to be playing again after such a long time without a guitar?

Good. Very good. I’m starting to learn again now, which makes me happy. I had to start from the very beginning. I am going to work and record again. I think I could do it now. I’ve been playing for six months and I’m picking up a lot of things that I overlooked before. I couldn’t practice for a long time ‘cos the strings were rusty or I didn’t have a guitar. Guitars have a real personality and some you get on with, others you just want out of the way.

I’ve been checking out some guitars, new ones. I’ve got three Fenders now – a Tele, a Strat and a Tele hollow body which I just got today. It’s beautiful. I also got a Howard Roberts Fusion from Gibson, the semi-acoustic with the sharp cutaway. It’s coal-black, beautiful, with two humbucking pick-ups.

I practise all afternoon, sometimes all day. I sit in front of the telly and watch the country music channel CMTV and play along. It’s great fun again, and some of them country players are fantastic.

Does it feel the way it used to?

No. No, not at all. Definitely not. The guitar used to speak for me in the olden days but I can’t let it do that for me anymore because I can’t let it break my heart again. The whole thing was that it used to be a bit of a show and I could get up and sing those sad songs. I meant some of it but not all of it.

What about ‘Man Of The World’? It has some pretty heavy lines in it like, “I just wish that I’d never been born.”

Yeah, I know what you’re saying, but that was a light–hearted sadness. It wasn’t a piss-take, I wish it was, but I had to make it light-hearted or else I would have been too sad to go on. I originally wrote it for the B-side, never expected it to be a hit at all. Don’t you laugh when you hear it? I think it’s a bit corny, don’t you?

I used to forget about Jeremy Spencer for some reason. I used to let [the rest of the band] do whatever they wanted and say whatever they wanted, to speak boldly. I probably owe them some money, now I come to think of it. I used to forget about Mick Fleetwood too. He just used to bop along with what you do. They weren’t getting broken by making the music, which was good because they lasted. I saw Mick recently. He put a record on the jukebox…one of mine, which was very nice of him…

You’re working on new songs. Is your approach different now that you have had to start again?

I see guitar sounds as colours and shades, pastels that you might use to paint a picture. It’s a melodic story. Usually it has a verse, maybe two, a middle, an instrumental break, sax or guitar. I’d put a movement over to the middle section, then back again to your original rift with a second break, then end. Simple idea, but it wasn’t enough. I went a bit crazy trying to do it.

But your classic tracks like ‘Oh Well’ and ‘Man Of The World’ have no choruses or middle eights as such, no sax breaks and are uniquely structured.

The thing about ‘Oh Well’ is that it was meant to be Parts 1 and 2 and people didn’t realise that the best bit was Part 2 on the other side of the record. You miss the best bit, the Spanish guitar break. The first side was what we played on stage. I didn’t think it would be a hit and I used to hate playing that one because we played the part that wasn’t as good. I wanted a bit of moody guitar playing. They wanted the bit that was easy to do, that everyone knew.

Does music frighten you still? You said in early interviews that music was often so complex that it frightened you into artistic paralysis.

That’s probably the difference now – I’m not afraid anymore. Music doesn’t scare me the way it used to. I don’t know if that’s good or not. I’m just beginning to learn.

I think the blues terrifies me still and I won’t do it and that’s certain. No blues, because it scares me.

You are supposed to have listened to Mark Knopfler’s playing once and commented how he made “so many mistakes”. Do contemporary guitarists still miss the mark for you?

Who’s Mark Knopfler? Oh, the bloke from Dire Straits. Well, I never said that, ‘cos I like him and his music. I might have said that as a joke, ‘cos I like a joke, but I think his playing is great. That’s the point, he doesn’t make mistakes does he? He’s actually one of the few players around I do like because he’s cheeky, isn’t he? Very saucy player.

I’m starting from scratch. I got forced to play for a group called Kolors. They were called White Sky at one time which was because of my album White Sky on PVK. My brother Mickey wrote most of that. It’s quite a good album, quite raw, very bluesy, not funky. Ronnie Johnson, he’s a good guitarist, plays Teles. I tell you who I like a lot and that’s Jesse Ed Davis. Played with Taj Mahal, played in Redbone, played with Lennon. I liked him. Red Indian bloke.

What’s your own view on spirituality and your own religious quests that had you wearing crucifixes and sandals in the late ’60s?

Jesus! I became a Jesus person. Yes, I believed.

Do you still?

No, not anymore. I was a Jesus person for a couple of weeks. I guess the angel of the Lord is a double blank.

You seem to dismiss your early work.

‘Man Of The World’, the lyrics are corny, hammy. Shall I tell you about my life?… My life! That’s Jewish for a start, isn’t it?!

I find it suspicious that they say things about my songs because I’ve never been anywhere like this before. How can they say it’s good when I’m just learning? I know now that my playing in the past was restricted. Compared to Wes Montgomery, I’m restricted.

John McLaughlin, now he’s good.

Good as Mclaughlin is, his playing is coming from a completely different place to you. It’s more technical, less passionate. Or am I wrong there?

But you can’t say that to a musician. You’re brave if you’d say that to him. Jazz is a scientific interpretation of the soul with some players. In others it’s just soul.

The soulfulness of your work is what people pick up on.

Hmmm, soul. My playing wasn’t about that, I don’t think. Otis Redding – he had a soulful guitarist, Steve Cropper. I was into Stax.

Do you still feel unable to express musically what you are? Are there still things that you want to say but can’t?

That’s a very good question. Yeah, I do. I’m still restricted and I can’t learn fast enough to say what I have inside. That was the problem in the beginning. I couldn’t play the things I heard in my head. It makes you want to give up sometimes. But now I’m learning better to do all the things I should have learned in the first place. I play every day.

You recently played your first gig in a decade at Frankfurt music fair. How do you find performing again?

I didn’t enjoy it too much. I had a funny feeling on the guitar when I went out. The rehearsal was beautiful, I could hear my voice perfectly and I’ve never been able to do that before. I didn’t have to sing loud, I could whisper. When we came to do the actual thing I couldn’t hear so well and I had to sing louder than I had to in rehearsal.

You did ‘Green Manalishi’, one of the songs that chronicles some of your mental problems. I thought you had vowed never to play it again.

Yeah, but I was persuaded to do it. I won’t do any of the old stuff, but I was persuaded to do it for just one show.

What’s your objection to the old stuff?

It’s past tense to me. Those are old, dusty songs. I did ’em enough times in the olden days and I should be allowed to move on.

Isn’t this just churlish when the world thinks they are classics?

No, because the new stuff will be better. Actually, it’s funny ‘cos on New Year’s Eve I was at a party and someone put on ‘Green Manalishi’ and this girl come up and asked me to dance. Dance to ‘Green Manalishi’!? But I got out there and you could dance to it. It has those heavy old African drums and it’s great but it’s not what I want to do live anymore. It’s that tribal ancient Hebrew thing I was going for. Ancient music. It’s heavy but it doesn’t tickle your soul much. At least it doesn’t tickle my soul anymore.

But ‘Green Manalishi’ is so haunting.

That wasn’t about LSD, it was money, which can also send you somewhere that’s not good. I had a dream where I woke up and I couldn’t move, literally immobile on the bed. I had to fight to get back into my body. I had this message that came to me while I was like this, saying that I was separate from people like shop assistants, and I saw a picture of a female shop assistant and a wad of pound notes, and there was this other message saying, “You’re not what you used to be. You think you’re better than them. You used to be an everyday person like a shop assistant, just a regular working person.” I had been separated from it because I had too much money. So I thought, How can I change that?

Now I don’t want to be with shop assistants so much and I know I wasn’t being true in those days, because I never was a shop assistant type of person. I thought they were a type when in fact they are just people who happen to earn their living being shop assistants. I never was a butcher or a French polisher. I did what I did, which was playing the guitar and singing. At the time I was worried. It wasn’t guilt; I was worried about me, which was wrong.

Is that why you gave all your money away?

I didn’t give it all away. I thought I’d come down off the trip when I was a Jesus person and that would be OK. But I’d left Fleetwood Mac and Clifford Davis [manager] said, “I’ve got money of yours and if you want I’ll set up a film so you can see what happens to the money when you give it to War On Want”, which is what I wanted to do. It was Africa or India and they were planting seeds and they had a tractor. I gave away all the Warner Brothers money, all our advance. Last thing at night they used to put pictures on telly of starving people and I used to sit there eating a doughnut and thinking, Why have I got this big stash that I don’t need when probably I’m going to die with it and all this is going on? Anyway, I got worried about what I was becoming, and it got to the newspapers and I was boasting about being righteous because I was on mescaline and I was feeling holy and compassionate. I had a vision of Biafra and gave the money away. I had what they needed. You know, why not give a little bit?

The Green Manalishi is the wad of notes; the devil is green and he was after me.

What kind of music will you make once you’ve learned how to play again?

All kinds of anything and everything. I like standards, Nat King Cole, nice melodies. I’ll probably end up there, I think. It probably won’t be the blues because I’m a bit too young for the blues, really.

Too young?

Yeah, I could do it at 22 but that doesn’t mean I was any good. I can listen to Hubert Sumlin but can Hubert Sumlin listen to me? Buddy Guy and Willie Dixon won’t listen to me. They don’t need to.

B.B. King said that while Eric Clapton and his ilk were good, you were the only white guitarist who ever sent shivers up his spine.

(Laughs) Oh yeah. That’s nice of him. I guess he’s talking about the tour we did with him back in the ’60s. I always thought that I was like a metal worker who should have been doing woodwork instead (laughs). I go in the ladies when it should be the gents. Life’s like that.

What do you remember about the time when you were sick? How bad was your mental anguish back then.

Anguish. Who told you that? It might not be true, you know…

What was the truth?

I dunno. I was kind of sick, I don’t know what it was. It was foreign, something that wasn’t me but lived in me. I felt very off-colour, very tired, under the weather really… (Long pause) I couldn’t put my finger on it. I felt seriously ill, I couldn’t get up. I was recording for PVK then, and it was terrible. My brother got a job as promo man for PVK and he said if you come on the label it will secure my job, so I did. They wanted me to sign a contract and they gave me an E-type Jag as my advance, but I pronged it on a bollard in the rain. I decided to get married to this girl, don’t know why. It was a very bad time. We went to Richmond for our honeymoon – which was where I lived…but we stayed in a hotel.

Does playing music again help you explain things better?

I relate to people through my playing. I relate better with the guitar than with words and I find it very hard sometimes to talk to people. Without knowing it, I relate to music people, people who know music and understand it, because it’s more subtle than words. There are no words for it and that is where all the difficulties come in.

Did you feel there was an artistic barrier you’d reached when you gave up playing?

Yes. I was frustrated by what I didn’t know and couldn’t do with my music. So I stopped. But the other side was that I had money or I was told I had money coming in and I didn’t have to work if I didn’t feel like it. I felt sick, so I didn’t do it anymore. Santana did ‘Black Magic Woman’ and the Fleetwood Mac royalties were good and Aerosmith did ‘Rattlesnake Shake’ so there was money. Then Gary Moore did one of mine.

Gary Moore still has the Les Paul you reputedly gave him. Do you want it back?

No, I don’t like Les Pauls anymore. Too jazzy for me. Too Parisian, too French. He’s welcome to it.

Why did you give your guitar away?

I had to go to hospital ‘cos I took too many LSD trips. I wanted the wisdom of LSD but I couldn’t quite get back again. I took one trip too many and I think it was the sixth one I took actually.

Why did you take the risk, having taken the drug a couple of times?

I didn’t take it out of choice, really. Someone just offered it to me and I took it. I should have refused it; I wish I had. I didn’t have the heart to refuse because they ask you in such a way that you can’t say no. It’s like you’d be saving a child from dying if you take this drug. It was very clever – would you take this, no money attached? I never paid for LSD. I rarely paid for any drugs. But I could take LSD and get very detached on it.

What did LSD do for you?

It took me somewhere where I wasn’t Peter Green and I had no cares at all, it was great. I wasn’t Jewish but I wasn’t not Jewish either. I couldn’t play around with being Jewish – which is what I was doing. It wasn’t that I was glad I was Jewish because we were God’s chosen people or anything, but it was OK.

Was being Jewish a big problem for you, then?

Yeah. People would call you names. They’d say stuff like

And God said unto Moses,

All Jews shall have long noses

Excepting Aaron,

And he shall have a square ‘un.

I was only about three but it stuck there with me and kept with me.

So you took LSD to escape…

Escape from Aaron (laughs).

But you never quite made it back.

No (laughs and pulls mock-paranoid expression).

You don’t feel back in the real world now?

No. Sometimes I make it back with the help of this girl who’s a spirit guide. They call it that but it isn’t really spiritual. She’s just into my head and knows its ways. It’s a secret of mine, we had an affair but I had to throw her out and she smashed a window, but it’s OK now.

You come back from your first few trips and it’s OK, but when you do six or seven and you have a few under your belt it gets more intense. Something happens to you so you’re not in control anymore. Someone else is.

Did you regret it or do you think you were going that way without drugs?

Yeah, oh yeah, and I wish I could go back to where I was before. One day I’ll punch that girl who gave me that acid. On the nose, two punches, very hard. Just to show her that it was you did this to me and I know it. Drugs are anti-violence but what they do to you can be ultra-violent. Heroin addiction is like that. I had friends who were addicts. People act and pretend about drugs, pretend it’s something it’s not, for effect.

(Pause) I’d like to try a Gretsch ‘cos I liked Eddie Cochran and Charlie Gracie. I like everything. I like melodies for all ages. I want to make music for all ages. Most people don’t want to hear the blues, they want a happy melody to make them feel good. East 17, I like them. That one that goes, “This is a record for my children/Deep deep down”, that’s a great record. Saw the video on TV (starts rapping lyrics).

The Red Hot Chili Peppers are good. I like their bass player, good guitarist too. He’s got a lot of energy. I like that one by that girl group where they sing ‘I Got Five On It’ [The Luniz – Ed]. They don’t wear much, do they? I like Toni Braxton too. It’s songs I like best. Something everyone can sing.

What about Oasis? Does their music go down well chez Green?

No. No, they haven’t got to me yet…Remember Suede? I didn’t like them either. ‘Animal Nitrate’! (Roars with laughter) I used to laugh me head off when that singer came on the telly. Was that a joke, do you think? Perhaps it was, in which case it was quite funny. Whatever happened to them? They just disappeared. (Sings) “Animal Nitrate whooooo whoooo.”

Soundgarden are great, their guitarist is something else, and I thought Nirvana were good, ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ was my favourite, but mainly because of the video which was really fast. I do like Bjork She’s amazing. Her first album was great from what I heard on MTV but I could only get a duff discotheque version when I went to the shops. It sounded nothing like it did on television. It had a good picture of her on it. I like that one, ‘Human Behaviour’. I don’t understand people who don’t like that record.

But I watch VH-1 now because MTV got sick with all the artwork. It was making me feel sick.

What did you think about The Egg And Potato Man who impersonated you?

He was a practical joke. He almost took EMI for a quarter of a million in an advance, but they called his bluff.

How do you prove your identity now?

I don’t have to because I am Peter Green.

*A WEEK OR SO LATER I MEET PETER AGAIN, ON THE SECOND day of his first proper studio sessions in nearly a decade, taking place at Francis Rossi’s state-of-the-art home studio. Overseeing Peter’s recording of The Shadows’ ‘Midnight for Twang’, the Hank Marvin tribute album, is Cozy Powell, a long time Greenophile.

Green looks tired, dark rings around his eyes and he stares blankly down at his empty beer glass. He talks to no-one and no-one talks to him. “It’s been a long day” whispers his manager.

I notice some copies of Razzle, Parade and other top-shelf monthlies spread out over the sofa. “They’re not ours, honest,” says Cozy, briefly embarrassed as he follows my glance. “Jesus, we don’t need that stuff, but it was very useful because Peter is such a perfectionist that he’d listen back to the track and say something like, ‘It’s not worthy enough, I want to do it again.’ Those of us with hair left were fucking pulling it out. You can’t argue with Peter if he doesn’t think it’s right, so we had to find him, er, well, a distraction.

“Basically, once he’d done a take we’d wave the mags under his nose and he’d be engrossed, meaning we could then listen back and work out which sections we wanted to keep and which we were going to have to drop in for. Peter won’t do drop-ins, he wants to always do the perfect take straight through and that isn’t going to happen. What we eventually got was a compilation of two takes and it sounds fantastic.”

Listening back to the mix it is immediately obvious that it’s Peter Green playing, even if it’s a straight copy of Hank Marvin’s original solo. Green makes it sound electric, unfathomably soulful and heartfelt. Towards the end of the track Green starts to stretch out and that melancholy sound, the sound that freezes you mid step, kicks in.

“That’s it!” cries Cozy “The Peter Green sound, right there…and I defy anyone to imitate that.”

Cliff Jones / MOJO / September 1996