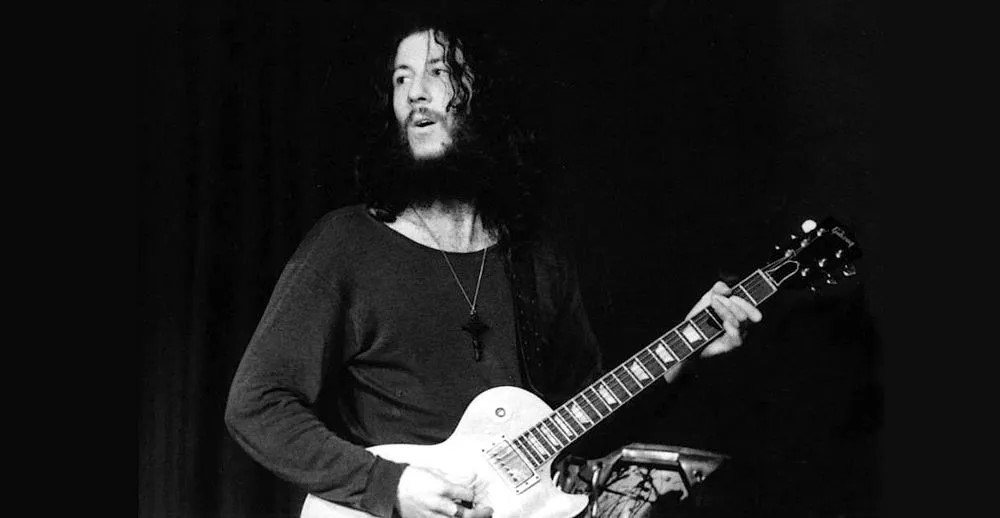

“I’ve never been on a plantation but I have been on a kibbutz.” Peter Green completes the Robert Johnson songbook, tours with John Mayall and spends two hours talking to Harry Shapiro.

About seven years ago, I wrote a two-part article on Peter Green for Record Collector magazine. In the course of the research, I had the opportunity to interview him. I declined. My mind went back to a horrible night at the Mean Fiddler in North London and a dreadful band called Kolors. Clothed in what can only be described as deck-chair chic, Peter mumbled a few lyrics and aimlessly strummed some indistinct chords before shuffling off. As far as I was concerned, Peter needed to be looked after but left alone.

So it was with some trepidation that I viewed the much-lauded Peter Green comeback. And those first few gigs in 1996 served only to confirm my worst fears, compounded by a later television documentary. There was one scene in particular at the office of the record company with a lot of banter and debate as to whether this or that track should be included. And in the middle of the rock-biz-talk, there’s Peter slowly closing his eyes as if to say, ‘Jesus, not this all over again’.

But since then, we have had the Robert Johnson Songbook which last year won a W. C. Handy Award for best comeback album. And also Destiny Road, produced by Pete Brown, an album about three songs from being a real comeback – no Peter Green lyrics, but some vintage licks brimming over with taste and subtlety. So, on the strength of music clearly gaining in strength, I went to meet Peter – in my view one of the finest exponents of modern blues guitar – at the home he shares with his manager Mitch Reynolds.

Peter is a rambling pony by way of East End Jewish wide boy. He talks in metaphors, tangents and time loops, speaking to me at one point of a “recent” Danny Kirwan song when in truth it has been many a sad year since the curse of Fleetwood Mac struck that frail musician with alcoholism and destitution. Peter Green is also seriously self-deprecating, his sentences peppered with laudatory references to Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton, as if the three major guitar heroes of the sixties were still slugging it out. Peter slipped through his schooling with barely a backward glance, “absolutely hated it; I didn’t have a clue what they were going on about.” Music was a different matter, “skiffle is close to the blues – ‘Alabama Bound’ by Leadbelly. That was one of the Lonnie Donegan things I was playing when I was ten or eleven. I was completely crazy when I first saw guitars, tea-chest basses and washboards. I thought, this is gonna be good. I want to have a go at this.”

Kicking off on guitar, he would stand thoughtfully watching Eric Clapton with the Yardbirds at the Crawdaddy Club (in Richmond). As a performer he played bass, but quietly honed his skills as a guitarist until he came to the attention of John Mayall, eventually taking Clapton’s place in the Bluesbreakers.

In June 1967, Peter was thinking about moving on, “they were a bit too powerful for me, too powerful. I had to have my guitar up loud to keep up. Also John had this jazz thing and he couldn’t entertain me with that at all. We’d done this song, ‘Leaping Christine’ (on the Hard Road album) and I thought, ‘this ain’t nothing to do with the blues.’ I thought it was a joke. If he’d laughed at the end of it, I would have been happy.” John had given Peter some studio time as a present and he had used it to record three tracks with Mayall band members Mick Fleetwood and John McVie, including ‘Looking for Somebody’, and Fleetwood Mac’. “I did think then that if I ever had my own band, I would call it Fleetwood Mac.”

What he actually wanted to do was to leave Mayall and go play on the South side of Chicago. “But Marsha Hunt put me off that. She said if I did it, some copper would pull me off the stage and ask to see my work permit which of course I wouldn’t have. Then instead I thought I might become the house guitarist for Blue Horizon which was just starting out then. Like Buddy Guy was for Chess, although that didn’t ring true for me. How could you have Buddy doing every solo; it would just become the Buddy Guy story.”

Today, Peter balks at the idea that it was the pressure of being the main man in Fleetwood Mac that pushed him over the edge, “A lot of people ask me about that and perhaps I had a different answer at the time. You can’t really say what it was all about – it’s Just ‘Showbiz Blues’ (a track on Then Play On), that’s the song that says it all. The rest of them looked like clowns, and I’m not part of the circus. Whatever Fleetwood Mac had become, I just didn’t want to play whatever it was.” The seventies and the eighties have been written off entirely as Peter’s lost years, although amid the gloom, there were odd glimmers of light on the early eighties PVK albums.

As Peter tells it, guitarist Nigel Watson finger-picking some Robert Johnson songs rekindled his sustained interest in playing. The nails were cut, the guitar dusted down and Peter began the slow haul of rediscovering that molten talent crusted over by years of illness and neglect. Peter went back to basics and it was probably natural for him to record the songs of the blues well-spring from which so much has come. Through playing Johnson’s songs, “I almost felt that I knew him,” although he typically brushes aside any comparisons between the hellhounds that dogged Johnson’s tracks and the green manalishis that lurked in the corners of Peter’s disintegrating sense of reality all those years ago.

The new album, Hot Foot Powder completes the Johnson canon. In his Radio 2 interview with Peter and Nigel Watson, Paul Jones asked the question why do another Johnson album, didn’t the first one say it all? Nigel began to launch into the “dedicated to the music” schtick, when Peter mischievously cuts right to the point with “the record company…” He didn’t need to finish the sentence. Peter’s refusal to buff up his work with a PR sheen even made it to the album cover itself. The record features guest appearances from Buddy Guy, Honeyboy Edwards, Dr John and Hubert Sumlin. Producer Roger Cotton says, “how proud and flattered they were that somebody like Peter would choose them for this album”; “Er, yeah,” says Peter, “but they were only being nice. What did you expect them to say?”

But, self-effacement notwithstanding, Peter gives a strong sense that there is a wealth of unfulfilled musical intent waiting for the right environment. He says he told the rest of Fleetwood Mac back in 1970 that he wanted to leave to learn the cello and compose classical music “and I still want to compose a symphony”. Interesting too, might be a situation where, instead of carrying the expectations of the Splinter Group, (“they won’t let me fall back, it’s hard, they want to stick me up the front all the time”) he was part of an all-star line-up. But so entrenched is the legend of Peter Green, chances are that the memory would still get in the way whoever was up there with him. Peter needs time to get to the place he would have been but for the long absence. Destiny Road may be the start of the journey. After all, nobody these days expects Eric Clapton to play 25-minute acid-blues guitar solos. And you can bet your boots Hendrix would not be setting fire to Strats.

So what are Peter’s expectations now? What does he want from those around him? In truth he doesn’t really know, “whatever it is, I haven’t found it yet.” And here is where a reservoir of high ambition leaks out from under the Hoover Dam of modesty, “just being professional ain’t gonna get you far with me. That’s just one of the 21 things you need to be to be a complete artist. I think I need to play with Jewish musicians because I’ve never been on a plantation, but I have been on a kibbutz.” So if you’ve got those ‘matzo ball, wailing wall, wide boy, no goy blues’, give Peter a ring. But you probably won’t pass the audition!

Harry Shapiro / BluePrint / June 2000